Standard Porcelain

by Jack H. Tod

Reprinted from "INSULATORS - Crown Jewels of the Wire", April 1973, page 25

In 1881 Thomas Edison invented the incandescent lamp, and in 1882 he

installed a 1200-horsepower generator in a New York warehouse and began

furnishing power (at 1300 volts DC to "subscribers" for operation of

electric lights.

Electric street lights were first installed in Syracuse, New York in 1882,

and in 1883 a New York grocer became the first person to use transmitted

electric power for a purpose other than lighting when he hooked an electric

motor to Edison's line and connected it to his coffee grinder. The first

electric railway came into use in 1885 when Richmond, Virginia converted 12

horse-drawn trolley cars to electric drive.

It was at about this time that R. Thomas & Sons, and possibly other

porcelain companies, started making "electrical porcelain" insulators

to facilitate the distribution of electricity from the generating stations to

subscribers. The electrical industry grew at an explosive rate during these

early years, and the numerous porcelain manufacturers of the period created a

large variety of insulators. The patents issued in the 1890-1900 period showed

that everybody thought he had an insulator knob or cleat which would be the

winning ticket.

Not only was there a general state of confusion in the types of wiring

insulators in use and the methods in which installations were made, but serious

electric shocks and fires were very prevalent. In an effort to end the chaos,

the National Board of Fire Underwriters founded the Underwriters' Laboratories,

Inc. in 1894 to formulate safety standards for the industry.

The National Electrical Code was first published in 1897 as the result of a

national conference of engineering and underwriters' organizations, and was

revised every two years by the Electrical Committee of the National

Underwriters' Electrical Association. One major section of the Code deals with

the materials, fittings and method of construction, and our interest here is

with the standards for the porcelain insulators - knobs, cleats, tubes, etc.

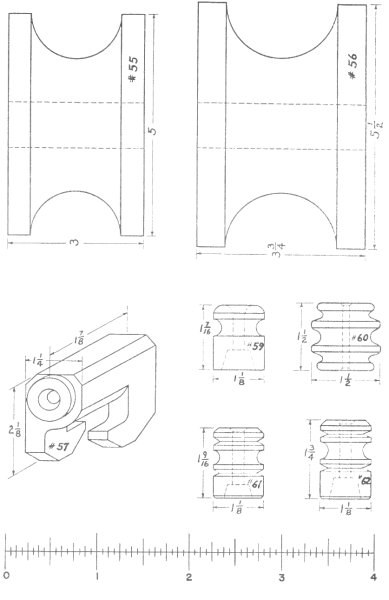

We are picturing in this article the "standard porcelain' knobs of the

Code, and I've made these drawings especially for this issue. The drawings are

1/2 size and the measuring scales full size if our printing work turns out okay.

There was one major revision of the knobs in the Code in the 1930's -

deleting some items, adding others and changing the dimensions of some knobs.

The sizes shown are generally the New Code (N.C.) ones, but both sizes are shown

for the #5 1/2. I have never seen very early copies of the Code and have no idea

of what the missing number knobs might have been, or even if they ever existed

at all.

This chart is nominally that for solid knobs, but the split ones normally

used an forestry insulators are shown. These are the Victor #22, the #37-Split

and the #38-Split. The ultracommon #5 1/2-Split is the proverbial "nail

knob" and will be the subject of a separate article in a later issue. There

were many more #5 1/2-Split knobs made than all the other knob shapes combined!

Manufacturers followed the Code in the more important and specified features only, such as hole diameter, groove size, etc. They

generally took off on their own with regard to unimportant details, such as

crown curvature, beveled corners, base counterbore shape, etc. There is also

some discrepancy between manufacturers on outline dimensions and on method of

numbering. For instance, some companies list the #3 1/2 in this chart as a #3

W.G. (wide groove).

As you can see, there was a standard knob for virtually every use. Nearly all

these shapes are common and can be found in the junk bins of secondhand stores

and electrical wiring companies. Some junk yards and salvage companies have

mixtures of this literally by the barrels.

Collecting standard porcelain "general" (every shape with every

marking) is practically hopeless; you need just about everything you see! A

representative collection can be had by collecting (a) one of every shape

without regard to marking and (b) one of every marking without regard to shape.

If this seems too confining, there are two good offshoot collections you can

build. Try to get every possible shape from one company such as Brunt, Findlay,

Knox, etc. Or pick a couple of pet shapes such as the #1 or the Victor #22 and

go after all the different markings on them.

Collecting "standard porcelain" is a real fun hobby for those who

enjoy the chase of collecting for itself. This is where we part company with the

big money boys and the antique store circuit. We do our collecting at old

abandoned houses, at flea markets, at junk yards , etc. The going price at flea

markets is a nickel apiece (or less) for the smaller items and maybe even a

whole two bits for a bigger goody. It once took me 3 full days to go through 4

barrels of this in the back yard of a secondhand store, and I bought the 75

pounds or so of goodies I picked out for a $5 bill.

In general we swap "standard porcelain" very casually. more or less

on the basis of "this here pile of mine for that there pile of yours".

But we do have some shapes and markings we don't trade away too freely, and we

have some items that we are outright chasing too. I know if I ever got all

standard chart shapes except for the last one, my wallet would probably start to

speak louder and louder.

For your convenience we have placed this chart where you can lift the staples

and remove it from the magazine for handy use in collecting these

"fun" insulators. Good luck, and see y'all at the flea market Sunday.

Jack

|